A Beginners Guide to The Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

I cannot tell you how many times patients say to me, “I had no idea the pelvic floor did all of that!” OR “Oh wow, I had no idea the pelvic floor was a group of muscles!” Even in the early years of my career I wasn’t really sure what exactly the pelvic floor was, or did. So, if you find yourself struggling to understand the intricacies of the pelvic floor, have no fear. I’m about to blow your mind.

The Basic Anatomy of Your Pelvic Floor

The pelvis is a ring of bones that is connected in the front through the pubic symphysis, and in the back through the sacroiliac joints (SI). These joints are supported by ligaments and cartilage that help to hold these joints together.

It’s possible for these ligaments to become irritated or loose during pregnancy and postpartum due to hormonal fluctuations. This laxity (looseness) can lead to pain and separation in the pubic symphysis (SPD), or in the SI joints (SI joint dysfunction).

Thankfully, we have the pelvic floor to help support our pelvis and to minimize the effects of ligamentous laxity.

Your Pelvic Floor Muscles

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles located at the bottom of your trunk. They attach to the bones of your pelvis and help support your internal organs (especially the bladder, rectum, and reproductive organs).

But that’s not all they do!

They also help control bladder and bowel function, sexual function, and are an integral part of childbirth. Much like other muscles in the body, they are capable of many different types of contractions.

The following are different types of contractions, from easiest to hardest:

- Isometric (lIke squeezing your buttcheeks)

- Concentric (like a bicep curl)

- Eccentric (slowly lowering your arm out of a bicep curl)

- Plyometrics (like jumping jacks)

The Layers of Your Pelvic Floor

There are three layers of the pelvic floor, and each layer has a different function.

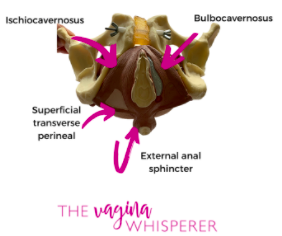

Layer 1

This is the most superficial layer, and involves the tissue from the perineal body all the way to the clitoris or the shaft of the penis (yes, men have pelvic floors too!).

The erectile tissues (clitoris and penile shaft), and the external anal sphincter are part of this 1st layer.

This layer is responsible for orgasm and arousal in both men and women, and lubrication in women through the Bartholin’s glands. Layer 1 also helps with sphincter control (closure) of the urethra and anus.

Tightness or overactivity of this layer can lead to constipation, difficulty urinating, or pain with arousal and orgasm. This layer may also become affected with tearing during childbirth.

Layer 2

This is just a bit deeper than layer 1, and contains all the muscles surrounding the urethra.

This layer (like layer 1) is responsible for bladder control and closure of the urethra. Tightness or overactivity of this layer can lead to urinary urgency, frequency, or difficulty fully emptying the bladder with urination.

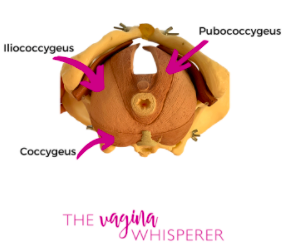

Layer 3

Layer 3 is the deepest layer. This layer contains a group of muscles called the “levator ani.”

These muscles function like a hammock to support internal organs like the bladder, rectum, and uterus.

Because it supports internal organs, this layer is most often discussed in regards to pelvic organ prolapse, and will be the layer we focus most of our treatment on in those patients.

The muscles of the levator ani group also function as postural muscles to help support and stabilize our pelvis and trunk with activity. When necessary, they can assist with rapid sphincter closure for those instances when we need to get to the bathroom in a hurry.

These three layers are also supported by ligaments, fascia (thick connective tissue), and other muscles that are not part of the three main layers.

Two main muscles that are in close anatomical relation to the pelvic floor and therefore should not be overlooked are the piriformis and obturator internus. Though these muscles are not truly considered to be pelvic floor muscles, they can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction and treatment of these may need to be included in the plan of care for certain patients.

Important Pelvic Floor Muscles

The Obturator Internus

The obturator internus is located deep to the gluteals (buttcheeks) and functions as a hip external rotator (rotate your hip out) and abductor (moves your leg away from your body). It lies next to the piriformis, and the sciatic nerve runs just between the piriformis and obturator.

If this muscle is tight, it can mimic sciatica. Sciatica is a common musculoskeletal issue characterized by pain radiating from the lower back down the leg.

When overactive or tight, the obturator internus can also mimic a condition called femoral acetabular impingement which is a condition of the hip that causes deep, achy groin pain, and a catching or pinching sensation deep in the hip. This muscle is commonly tight in distance runners, Crossfitters, and other sports when the limb is consistently in external rotation and/or abduction.

The Piriformis

The piriformis is another muscle that is located deep to the gluteals. The piriformis is also responsible for external rotation of the hip, as well as stabilization of the femur (thigh bone) in the acetabulum (hip socket).

Much like the obturator, if overactive, it can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction and become a site for sciatic nerve entrapment. Again, like the obturator internus, the piriformis is commonly tight in athletes who are participating in activities that are consistently putting the hip into external rotation.

The Big Picture

All of these structures (bone, muscles, and connective tissue) play an important role in maintaining optimal function of our pelvic floor, and therefore it is important to assess all of them in evaluation. Each tissue should be considered when determining a treatment plan.

The good news is that a pelvic floor physical therapist can help treat dysfunction in any of these areas in order to help you return to your desired function. These tissues can be treated through a combination of internal and external tissue release (massage, myofascial release, or trigger point release), muscular retraining (relaxation, strengthening, or both), and activity modification (even if just temporary).

So, if you suspect that you might be experiencing pelvic floor dysfunction, or have not seen improvement with conventional outpatient physical therapy, you should give pelvic PT a try. There are many treatment interventions that can be utilized to get you moving again without pain or other debilitating symptoms.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Interested in more tips on how to prevent or overcome Pelvic Floor Problems?

Download this free guide for some simple, do-able, totally-not-weird tips to take better care of your down there.

___________________________________________________________________________________________